Read this article about a class at Virginia Commonwealth University where design students work with students from fashion and interior design to address issues in their community…

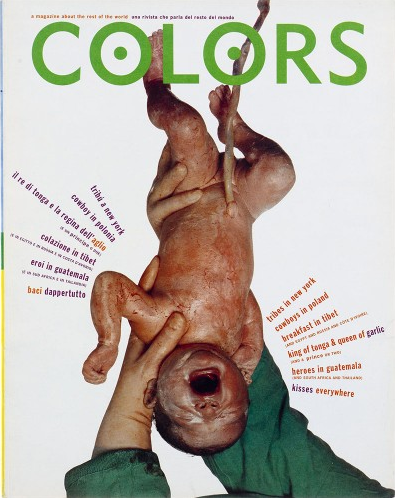

A college student stands inside a papier-mâché ball known as Snorticus from Orticus, attempting to blow a vuvuzela until he’s red in the face.

Seated around him in a cavernous classroom at 207 E. Broad St., fellow Virginia Commonwealth University students laugh at the absurdity of his sputtering, until a teacher grabs the long plastic horn, the kind often seen at sporting events, to show him how it’s done. They’re witnessing a costume preview of an outlandish character from a fashion show the students created.

Welcome to Middle of Broad, or MOB studio, an interdisciplinary class where it’s required to think outside the box. The class takes the energy and creativity of students and matches them with local, professional mentors and volunteers to strategize, build and incorporate good design projects for a healthier Richmond.

They’ve done MOB moments, in which each team designed a bus stop and built a prototype in a week. They’ve worked with the city bike and pedestrian coordinator to design a bike rack in front of 205 E. Broad St. Another project developed soft seatbelt covers for the tender sites on chemotherapy patients’ bodies. The Massey Cancer Center is now producing them for patients.

This semester some of the projects already scheduled include working with Rag and Bones Bicycle Co-Op in Scott’s Addition to help transform an underused parking lot into a bike-in outdoor movie theater. They’re also working on creative ways to develop a wrap to protect a water tower near Broad Street and the Boulevard.

Founded in 2012, MOB is the brainchild of three VCU faculty friends — Kristin Caskey from fashion, John Malinoski from graphic design and Camden Whitehead from interior design.

Each semester, the faculty makes sure students are involved in public housing communities and other neighborhoods they might not normally visit. One team has worked on a branding project for Lillie Estes, a longtime community strategist in Gilpin Court. “Their design work was secondary to the working relationship and bond they established with her,” Whitehead notes. Another team worked on alternatives for affordable housing on an abandoned property in Mosby Court.

click to enlarge

- Photo: Ash Daniel

- The costume for Snorticus from Orticus sits awaiting an out-of-this-world fashion show that was held Friday, Feb. 5.

“VCU, as an institution, often exists as the 500-pound gorilla in the city, expanding where it wants, moving into long-established neighborhoods, sometimes callously,” Whitehead says. “[The school] has gotten better at engaging the city but re-establishing trust is a long and slow process.”

But the studio can be more nimble in its community outreach, Whitehead says: “We meet citizens and civic groups one-on-one and listen and respond. There is no larger agenda except to make the city a better place through design.”

To that end, the studio class shares space with the local nonprofit Storefront for Community Design, which recently celebrated five years of providing low-cost design assistance to anyone who needs it in the city.

“We’re connectors for clients — basically equivalent to legal aid or free clinics for architecture, design, implanting,” says Ryan Rinn, executive director of the nonprofit and a planner by trade. “We make sure to mention MOB studio is an option and what they do is a little more in-depth.”

“This is a class that runs like a design studio in the real world,” Caskey says. “I think as far as a big dream, we would love to have this become a place where students graduate from the nation’s top school of arts and design and stay in Richmond to become designers by having fellowships where they really serve the city.”

The need is there: Caskey says they’ve had more clients than they can serve every semester for four years now.

The studio also reaches beyond Richmond. One venture this semester will involve assisting a predominantly black community of Emporia in preserving the ruins of the Greensville County Training School, a Rosenwald School. Students will help craft a vision to preserve the ruins while creating an outdoor event venue that serves the town.

“Design is more than what’s in a high-end Shelter magazine,” Malinoski says in a series of haikulike emails. “We are providing design services for those outside of design. … Human power makes it go.”

That’s not to say projects don’t get controversial. Last year the class took on Monument Avenue as a speculative project, with the goal of using design to deepen the conversation that arose out of racial incidents in Charleston, South Carolina, and Ferguson, Missouri. Students adopted a fictitious design competition format as an entry point into the national debate about Richmond’s Confederate heritage. Ideas were as wide-ranging as turning the monuments upside down, shrouding them in smoke or covering them with kudzu.

“Design realizes our values,” Whitehead says. “It’s important that students see the many roles that design can play in the city — as healer, as provocateur, as problem solver, as an economic driver. MOB allows them to see the complexity possible in the smallest and simplest of projects.”

Last semester, Michael Walker, the student with the vuvuzela issues, worked on a re-brand of the logo for the Virginia Anti-Violence Project, which works to end violence in the LGBT community.

“MOB is giving us real-world experience. The students want to be here and engaged in the community,” he says. “We’re learning that designers can help people.”